How racism within the healthcare industry is only further exacerbating racial inequality and medical care across the United States

By Grace Yoo, Princeton ’26

“A Black woman is 22% more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71% more likely to perish from cervical cancer, but 243% more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes.”

In other words, pregnant Black women are 3 to 4 times more likely to die as a result of pregnancy-complications than white women, and according to the CDC, most pregnancy complications are preventable.

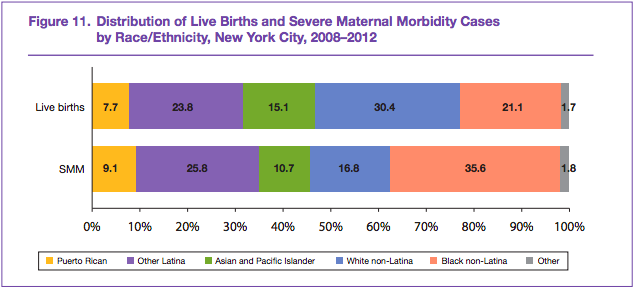

A recent study done by the NYC government in 2016 takes complex factors such as age, race, socioeconomic background, education status, etc into account in order to better understand why pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. have been increasing despite advancements in technology. In short, the study reveals that Black women living in high-poverty zipcodes were most likely to perish as a result of a pregnancy complication. There is no doubt that there is a lack of access to high-quality healthcare if you are impoverished. However, Black women, regardless of their socioeconomic background and education status, are still at the most risk of severe maternal morbidity.

Take Shalon Irving’s story as an example.

Shalon Irving was a 36-year old epidemiologist for the CDC who studied to better understand how inequality and violence made people sick. Rashid Nahj, Shalon’s mentor from the CDC, says “[Irving] wanted to expose how people’s limited health options were leading to poor health outcomes.” Not only was Shalon Irving a CDC epidemiologist, but she was also awarded with a B.A. in sociology, two master’s degrees, dual-subject P.h.D., and title of lieutenant commander of the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service.

Despite Irving’s notable status and education from Johns Hopkins University, she still unfortunately and tragically passed away three weeks after giving birth to her newborn daughter Soleil in 2017.

Irving had suffered from years of fertility issues, a blood-clotting disorder, and uterine fibroids before her pregnancy. Not to mention, Black women are at a higher risk of postpartum hypertension and peripartum heart failure, which calls for closer monitoring and patient care from doctors.

Regardless, Irving’s doctor had sent her home after a test for postpartum preeclampsia came back negative without any treatment. When Irving went back to the doctor complaining of malaise and swelling in her right leg, her doctor sent her home again with only a prescription for hypertension. The very same day, Irving was rushed back to the hospital due to a heart attack, and a week later, she was removed from life support. She had died due to complications of high blood pressure, which were completely preventable. (source)

Irving’s story is one of the many regarding Black mothers. One such story is from a mother from Nebraska who tried to convince her doctors that she was having a heart attack despite her history of high blood pressure. Her doctors only began treating her after she had begun suffering from another heart attack. Additionally, a pregnant young mother from Florida was told her breathing problems were a result of obesity when, in fact, her lungs were filling with fluid while her heart was failing. Another Black mother from Arizona was accused of smoking marijuana by her anesthesiologist because of “the way she did her hair.” A Black Chicago woman with “a high-risk pregnancy” was so upset by her doctor’s attitude, she changed her OB/GYN during the beginning of her last trimester, only to pass away from a postpartum stroke. Even Serena Williams almost suffered a similar fate.

So why are Black mothers so disproportionately affected by child-birth related deaths?

For decades, the disparity in healthcare was attributed to Black people’s “susceptibility to disease” and their “behavior.” That notion is inherently wrong. Race is not the problem. Racism is, and many sociologists and doctors would agree.

It is a known fact that people of color do not get the same type of access to quality healthcare. There are many reasons as to why this is: stereotypes, gentrification, poverty, lack of inclusion of skin color in medical textbooks/training, etc. For instance, dermatology is the prime example of a field that requires changes in training. Symptoms such as rashes often manifest differently in Caucasians than in African Americans. However, physicians and clinicians commonly cannot recognize these differences in rashes or other symptoms, resulting in ineffective prognosis and misdiagnosis. This is true for preventable or treatable diseases such as Lyme disease, psoriasis, lupus, melanoma, and even “life-threatening drug reactions”. Authors and publishers of medical textbooks also need to do a better job of representing people of color and how symptoms of these certain diseases show up on pigmented skin. According to one study, only 4 to 18% of textbooks contain dark-skinned images. Additionally, in 2017, one nursing textbook, Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning, included a segment on “Cultural Differences in Response to Pain”, claiming that Black patients “report higher pain intensity than other cultures” and that they “believe suffering and pain are inevitable,” fueling racial stereotypes and inappropriately displaying people of color.

Thus, Black women and mothers do not have their pain taken seriously by doctors or nurses, and the vast majority of maternal complications can be attributed to chronic stress that indisputably arises from racism and discrimination.

“Weathering” is a term used to define the impact that stress has on the mind and body, and it (again) disproportionately affects African American women. Weathering, or chronic stress, leads to other chronic illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes and can even result in telomere shortening or preterm birth, which African American women are 49% more likely to experience than white women. To add on, Black women in their 30s are more predisposed to preeclampsia than white women in their 40s.

Black women deserve and require personalized and attentive care, and in order to ensure that all people of color get the same quality of care as others do, we must work to identify racist attitudes and behaviors and eradicate them. There are other ways to help such as going out to vote for advocates of affordable health insurance, paid maternal leave, and expanding high-quality healthcare.

RESOURCES TO HELP

GoFundMe for Single Black Mothers

GoFundMe for a Homeless Postpartum Mom who Lost her Child

Glossary

Uterine fibroids: growths on the uterine wall that are not cancerous

Postpartum hypertension: high blood pressure after giving birth

Peripartum heart failure: weakening of the heart that often occurs during late pregnancy and after delivery

Telomeres: parts of our chromosomes that indicate life expectancy

Preeclampsia: complications that involve high blood pressure and having protein in your urine